Michael McConnell’s Version of Federalism

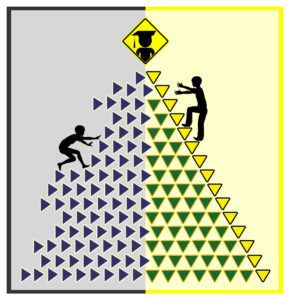

National Pork Producers Council v. Ross may be one of the most consequential cases of the Term, and I don’t just mean for the price of pork chops. A few states, most importantly California, are such large markets that—if the Supreme Court does not intervene—they can impose their notions of proper standards of production on every other state in the Union, at little cost to themselves. Because nationwide producers often cannot segment their markets, producers will be forced to follow California rules for the whole country, or face the crippling consequence of exclusion from the California market. Add to this the fact that these large states—California, Texas, New York—are also one-party states, whose views on social policy are often at one or another extreme. More moderate Americans in other states will be governed by laws they would not vote for, if they had a chance. This is contrary to the democratic postulates of our federal system. This is from Eugene Volokh, “From Prof. Michael McConnell (Stanford) on the Dormant Commerce Clause,” The Volokh Conspiracy, October 11, 2022. Professor McConnell, as Eugene Volokh points out, “is one of the top constitutional law scholars in the country.” On this one, though, I wonder. My disagreement has nothing to do with whether the law in question is a good one; I think it’s bad and I voted against it. But sometimes federalism allows bad laws. In reading over this brief, I was reminded of the great title that James Buchanan chose (I assume he chose it) for his critique of the first edition of Richard Posner’s Economic Analysis of Law. The title: “Good Economics–Bad Law.” Except in this case I’m not even sure it’s good economics; more on that anon. The Law But now to the law. If it were true that the California law “forced” (McConnell’s words) producers in other states “to follow California rules for the whole country,” then he would have a point. But nothing in the law forces them to do that. I use the term “forced” literally; McConnell apparently does not. Producers in other states are free to produce for 49 states plus D.C. and not sell to consumers in California. He calls this a “crippling consequence,” but is it really? McConnell notes that Californians “consume 13 percent of all pork produced in the United States.” Is is really crippling to forego 13 percent of a large market? I don’t see it. The essence of federalism is that voters and politicians in various states get to decide on the regulations and laws in that state. There are certain constraints, of course, that the U.S. Constitution imposes. But McConnell doesn’t succeed at saying why the U.S. Constitution forbids California voters from voting to allow only certain products to be sold in the state. It’s not as if the California government is discriminating against out-of-state producers; it applies the same rules to all pork sold in California. McConnell does make one possibly good legal argument. He writes, “California regulators will roam the land inspecting farms in other states to enforce the law.” If that were true, then he would be right: this would be a state restriction on interstate commerce. It’s hard to see, though, how it would be true. Wouldn’t every pig farmer outside of California be legally able to say, “Get the hell off my land.” Notice that McConnell tries to bolster his argument by pointing out, correctly, that California is a one-party state in which many people’s views are “at one or another extreme.” Don’t I know it, having lived in this wacky state continuously since 1984. But why should that matter under federalism? Isn’t one of the major points in favor of federalism that it allows for diversity of policies? The Economics Now to McConnell’s economics, which I think is suspect on two counts. First, monopsony. McConnell writes, “Once California is green-lighted to use its monopsony power to pressure businesses all over the country to comply with Californian social preferences, there will be no end to it.” But does control over 13 percent of a market constitute monopsony? I think that’s a reach. Second, on who will pay the cost. McConnell writes, “A few states, most importantly California, are such large markets that—if the Supreme Court does not intervene—they can impose their notions of proper standards of production on every other state in the Union, at little cost to themselves.” Elsewhere McConnell argues that this law will substantially raise the price of pork. My guess is that he’s right. So how, exactly, is it that we Californians will bear little cost? Note to Commenters: I have found, when I’ve commented on legal issues, that people, especially lawyers, tell me to stick to economics. But that’s not an argument. Notice that I didn’t say that McConnell shouldn’t make economic arguments. Rather, I challenged his arguments, showing how weak they are.There’s a reasonable chance that I’m wrong about the constitutional issues here. If so, say why. (0 COMMENTS)