The observation of social phenomena, sometimes apparently innocuous ones, can help confirm theories of society or invalidate them. I found an interesting story about residential generators in Kris Frieswick, “Your Generator Is Noisy as Hell. But Your Neighbors Don’t Have to Hate You for It,” Wall Street Journal, July 18, 2024.

A residential generator is useful during a power outage, and close to essential if you are working from home. Properly speaking, no single good is literally “essential” as substitution possibilities always exist. One can bring his laptop to work in whatever coffee house or eating joint that still has power and offers power outlets. But for many, nothing beats a residential generator.

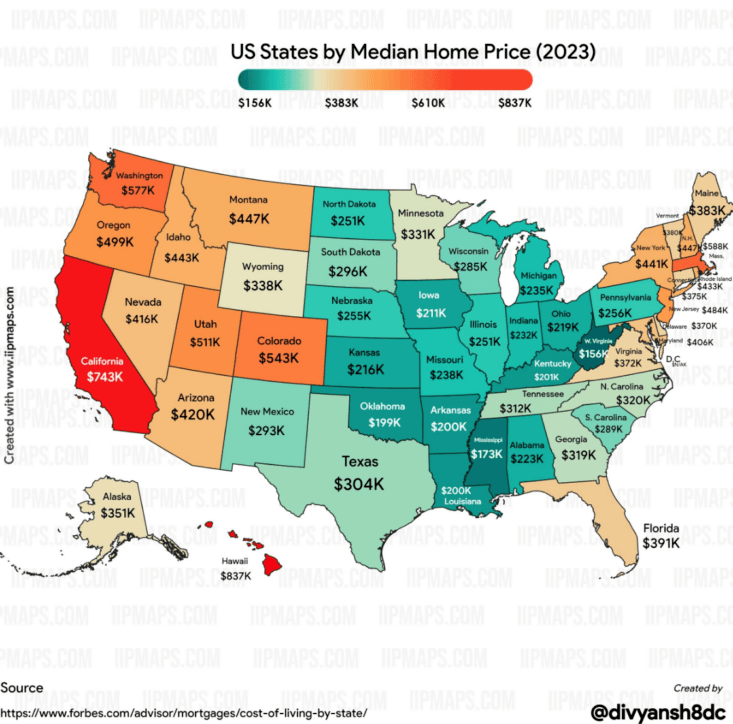

Indeed, many American households own one, portable or standby. Those who don’t obviously made different choices, for a number of reasons revolving around personal preferences, prices, and incomes. Not many households in America would find it very difficult to sacrifice some other consumption goods, services, or activities to purchase one, even if its connection to the house electric system will add at least $1000. Most people elsewhere in the world don’t have these opportunities, and it is not because of capitalist exploitation!

In rich countries and places with high population densities, residential generators are sometimes difficult to use. I suppose that most landlords do not accept generators on apartment balconies. They remain useful in isolated areas and in neighborhoods of single-family houses or duplexes.

One problem, which is the topic of the WSJ story, is that the noise of a running generator may annoy neighbors. Perhaps envy reduces the tolerance of those who are stuck in dark houses with no heat (or air conditioning), and no power for the freezer, dishwasher, and so forth. But in a free or more or less free society, a generator’s owner will reason that he is on his own property; his neighbors will normally understand that too. The noise can be considered an externality (perhaps) if outages happen often or when they last a long time. Otherwise, it will not be unexpected—contrary to, say, mowing the lawn at night, which would be a real nuisance. Moreover, except if your neighbors are really close or live in a tent, the noise is supportable, even for the generator’s owner who hears it from much closer.

We see that private property accomplishes its function of minimizing conflicts and facilitating life in society. In my Maine suburb, it would be surprising if a neighbor complained about a generator’s noise during a power outage. In fact, I had never heard about this possibility until I read the WSJ story.

Now, if some neighbors are upset, the generator owner can compensate them, even if indirectly; The journalist writes:

Lastly, work some bribery! During outages, offer to refrigerate your neighbors’ frozen steaks and ice cream. Put a power strip on your deck so people can charge their devices. Share your wifi password. In prolonged outages, give away ice. Have a movie night. The longer the outage, the more valuable these gestures will become. If the outage goes on long enough, your neighbors may grow to enjoy the sound of your generator, knowing they can sign into your wifi and download some eps of “Frasier.”

What is interesting with these suggestions is that they represent normal behavior in a commercially-minded and free (or rather more than less free) society, where everybody is accustomed to free exchange and voluntary cooperation. When it breaks no contract or major convention, a “bribe” works just like the price in an ordinary exchange. (On conventions, see Anthony de Jasay’s Against Politics, especially Chapter 9.) Similarly, we can view every price in an exchange without fraud as an honest bribe. A bribe is more civilized and more efficient (in the economic sense) than a jail or fine threat or a boot kick.

(0 COMMENTS)